My Oxford tutors were not in favour of the year abroad: reading the complete works of Montaigne in the college library was far more their idea of studying Modern Languages at Oxford than actually visiting the country, and heaven forbid, speaking the language. I wanted to go to Germany, but my French tutor spread the word around that there were ‘treacherous noises coming from the Thomas camp’, and I settled on France. I got a post as English Assistant at a lycée in Marseilles, and wrote joyously to my ‘French mother’, Madame Martel, to tell her. Her reply was full of foreboding: Marseilles was a dangerous place, full of gun-toting mafiosi, and she would not be at all happy for one of her own daughters to go there. She warned me to be very careful.

Undaunted, I set off for France. The first few days were spent in Paris, attending, or rather not attending, an induction course at the Sorbonne. I befriended some other English girls, which was just as well, as everywhere we went we were the objects of male attention. Not being good Catholic girls and all presumed to come from swinging London, ‘les petites Anglaises’ had a reputation for free love. This, combined with the appeal of the exotic, albeit a rather proximate exotic, was apparently irresistible. We spent one afternoon in the Tuileries gardens, hopping from bench to bench to avoid unwanted admirers. Then we took the train south, only to find it was full of sailors returning to port, who delighted in annoying us all night: ‘When you’re angry your eyes burn like dark coals’.

After this exhausting journey I was glad to be taken in by one of the English teachers, Madame Deforge, for a few days. Madame Deforge was blonde and elegant, and unhappy. She had two small children, and her husband was some kind of Inspector of schools. He seemed much older than her, and rather formal. Meal times were tense affairs as Madame Deforge struggled to make conversation while her husband maintained a more or less stony silence, and the children whined. She was always débordée, overwhelmed by her work as a teacher and a mother. She explained that May 68 had split people into two camps. Clearly she and her husband were in the wrong one.

The day after arriving I went to the lycée, where my trunk had already turned up, causing some consternation because of its size and outstanding customs duties. I nonchalantly signed forms and handed over money, and set out on my search for somewhere to live. I found a room right next to the school, on the rue Paradis. Its only drawback seemed to be the traffic noise, which was loud, even on the fourth floor. The room was very provençal, with red hexagonal tiles on the floor, dark green patterned curtains and bed cover, and yellow cushions. Madame Grandjean, my landlady, explained that I would have to use the shower in their flat, and that I should avoid Mondays, when she hung the washing out in there. With fear in her eyes she also told me to avoid what she called the quartier arabe, and everywhere in Marseilles to keep my handbag well tucked underneath my arm. This latter piece of advice was illustrated by Madame G. clutching her rather large bag tight against her equally voluminous body, eyes darting back and forth.

I was given a timetable of twelve hours of English conversation classes each week. One day I started at 8am, so living next door to the school was a distinct advantage. I would get up as late as possible, heat up milk on my camping gas stove to make a cup of nescafé, gobble a croissant or a bit of baguette, and put on my teaching clothes: my pink jumper and new navy polyester trousers from Marks, which had white stripes and an anchor motif at the ankle. They were just the thing, I thought, for teaching English in Marseilles: smart, but with a hint of the nautical.

Four hours later I would emerge, exhausted by my efforts to make silent French adolescents speak English. The Head of English introduced me to one class as having ‘almost the Oxford accent, but not quite’. I thought this was a bit of a cheek given his own tendency to pronounce the mute ‘e’ in words such as saucepan, à la marseillaise. His pupils were of course impervious to the comic effect of this on the English ear, and I was alone in stifling a giggle. One small group of boys, science and maths specialists, were timetabled to see me on Saturday mornings. They came every week, curtailing my weekends, and never uttering a syllable, unless I made them read aloud, in accents that made the saucepan teacher sound like Laurence Olivier. I tried to make the lessons as boring as possible, to stop them coming, but nothing worked, and through the whole school year they attended diligently.

Another, much bigger class was livelier. Their sole interest was Chairman Mao, and if I said anything about England they would quickly interrupt to guide me back to the topic of China and the Cultural Revolution, about which I knew nothing. When I described this to Madame Deforge she was quite horrified: ‘we have not brought you over from England to talk about China!’.

On weekdays I ate lunch in the school canteen, where for two francs fifty I could get what seemed to me to be a gastronomic meal. At the entrance to the canteen there were sinks with yellow bars of soap on metal prongs sticking out of the wall above them. The other language assistants and I were much struck by the foreignness of this arrangement, and the Italian, Claudia, called them les savons phalliques. It took me a while to work out what this meant. Over lunch we heard more May 68 stories, mostly from the perspective of the camp that Madame Deforge did not belong to. Again, it took me some time to work this out.

The left-wing staff who ate in the canteen seemed to quite like us foreigners, and every day after lunch we all went to the café opposite the school, chez André. One day, an international meal was proposed, and the school secretary and staunch communist party member, Arlette, offered her flat as the venue. The first course would be the responsibility of Italy, though Claudia recruited me and the other English Assistant, John, to make the béchamel for her Lasagne. France would take care of the main course, pork simmered in milk with provençal herbs, and green salad. England would do dessert, and I proposed trifle. Austria, Spain and Russia were exempted from cooking and required only to bring wine. A date was fixed and I wrote to my mother to ask her to send me packets of Rowntrees jelly and Birds custard. She sent my not very raw materials at great expense. Gastronomically, the meal turned out to be a bit of a disaster for every country except France. John and I had never made béchamel before in such large quantities, and we burnt it, so that the Lasagne had an odd flavour. Claudia was very cross that we had ruined her and Italy’s reputation. Then my jelly did not ‘gel’, despite being left in the fridge overnight, so a crucial component of the trifle was missing. The French could not understand why I was making crème anglaise with powder from a packet, despite my explanation that this was really the only way to make custard. Nonetheless, what we lacked in culinary skills we made up for in conviviality and consumption of wine, and the lunch went with a swing. Our French hosts were perhaps secretly pleased that their gastronomic superiority had been confirmed.

Chez André I also made the acquaintance of the Russian teacher, Monsieur Vibert, and he and I often lingered there in the afternoons, long after everyone else had left. One day he pointed at the table and said ‘there is a barrier between us’. The deep meaning of this statement escaped me. He also taught me to say in Russian ‘I am melancholy and alone, and there is no-one I can reach my hand out to’, spending some time perfecting my pronunciation. Monsieur Vibert was unlike the other teachers: he did not have a house or a flat, or a family. He lived with his Alsatian dog in a chambre de bonne, a former maid’s room, with shared lavatory and shower on the landing. One day he and I ate dinner together. He said he wanted to eat brains, and that you could get a version of this delicacy in the épicerie over the road. We went up to my room, and I fried the brains in butter on my gas stove, paying scant attention to what I was doing. I sat on the end of the bed, while Monsieur Vibert perched on a stool, and my trunk served as a table. We ate the brains and continued our philosophical discussions, while the dog slept at our feet.

One night shortly after this I was feeling miserable and homesick. The rue Paradis had taken on a rather hellish dimension. That day Madame Grandjean had told me off for having a shower on a Monday and cooking something other than a boiled egg in my room. When in response to her interrogation I told her I had been heating up stuffed cabbage from the charcuterie, she was outraged and said I had made the whole flat smell. That evening I sat on my bed in my night clothes: a very short pink and white frilly nylon nightie and my black kaftan, and tried to read, but tears kept running down my cheeks. Then I heard a loud whistling noise outside above the din of the traffic, so I opened the shutters. Down below in the street was Monsieur Vibert, signalling to me to let him in. I ran down the dark staircase and he and the dog came in, and up to my room. Once there he clutched me in a violent embrace, and managed to get me out of the kaftan and almost out of the nightie, before I stood up and asked him what he was doing. There followed a long declaration of love. Since the first time he had seem me signing for my huge trunk, my smile revealing my two ‘typically English’ large front teeth, he had taken a shine to me. He wanted me to be his lover, and would take me to the restaurant, to the theatre. When I said I already had a boyfriend at home and in any case had never seen him in that way (after all, Monsieur Vibert was thirty years my senior) he became angry. He had already seen everything he said (and it was indeed true that the pink and white nylon number was pretty revealing), so I might as well go the rest of the way. Then he interrogated me about the precise nature of my physical relationship with my boyfriend: ‘have you had sex?’. I equivocated: ‘yes and no’. Enraged, Monsieur Vibert continued ‘Has he entered your body, yes or no?’. I was forced to admit to my virginity. ‘So that’s why you have spots!’ he exclaimed, ‘it’s not natural’. As far as I was concerned, this was the end of Monsieur Vibert’s chances, which in any case had rested largely on my need for a comforting cuddle, and certainly did not involve any further thrusting of his tongue down my throat. Spots and big teeth! This was not the way to make a girl feel desirable. When he realised that I was not going to give in, Monsieur Vibert explained at some length that he would never speak to me again, and stormed out of the room.

The next day, as soon as I could get John and Claudia on their own, I poured out the whole sad story. They were horrified, especially when my story was confirmed by Monsieur Vibert’s failure to appear chez André after lunch, a failure that was repeated every day for the rest of the school year. John and Claudia decided that such an ingénue needed to be taken in hand. Claudia explained that in France as in Italy you could not invite a man to your room to eat brains and then refuse to sleep with him. She also decided to take charge of my fashion choices, explaining to me that it was best to choose neutral colours and avoid pattern, and that trousers should be well cut, as hers were. She frowned on Polyester, preferring linen, wool and cotton. Some of her trousers were even lined, and had to be taken to the dry cleaners. This seemed an awful lot of trouble to me, but I had to admit that Claudia’s trousers did fit in a way mine simply did not. Warming to this theme, John burst out that there was something bizarre about all of my pantalons. When I asked him what he meant he just said, ‘well, the ones with the anchor’, leaving me quite crestfallen, as I stirred my third cup of hot chocolate chez André.

I also needed to sort out my accommodation. Madame Grandjean was getting nastier by the minute, and the early days when she invited me to dinner, or to watch Princess Anne’s wedding on her TV were a distant memory. She did let me use her ironing board once, but when she saw my efforts to iron a pleated skirt, commented that ‘in France we are rather more careful about such things’. After that I gave up on ironing. Madame G. became convinced that I had a boyfriend living with me in my room. Perhaps she had caught a whiff of the Alsatian on Monsieur Vibert’s ill-fated visits. Her accusations and my astonished denials were the substance of several unpleasant scenes. She also told me that I had far too many showers, and should use the basin and rather nasty plastic bidet in my room. I told my friends at lunch how unhappy I was, and they came up with the suggestion that perhaps Monsieur Rolland, one of the science teachers, and his wife might have a room in their house in rue Notre Dame des Anges, as their sons had left home. They did, and with John’s help, I triumphantly carried my trunk out of Madame Grandjean’s flat, while she shouted at us for leaving doors open: ‘Ce n’est pas une gare ici!’.

My new room was light and airy and at the top of the house, with, blissfully, its own bathroom. It looked out over the pins parasols at the back of the lycée, and the red-tiled rooftops of other houses. My new landlords were charming and relaxed, and a happier phase of life began. If paradise had turned into hell, I was certainly now living with the angels. Rue Notre Dame des Anges was part of a network of winding streets that seemed more like a village than part of a big city. At the top of the hill perched Marseille’s most iconic monument, the wonderfully kitsch church of Notre Dame de la Garde, with its ships in bottles and prayers for salvation on the seas.

In February Claudia returned from Turin in a Fiat 500. We toured Provence in this tiny vehicle every weekend, staying in hotels without stars where nonetheless the sheets were scented with lavender and the red-tiled floors polished. In Vaison-la-Romaine we saw almond trees in blossom, snow-capped mountains in the distance. Near Apt in haute Provence we stayed in a youth hostel built into the hillside. Tree roots intertwined with the stone walls. We awoke the next morning to a strange light, and had to dig the Fiat out of thick snow before we could leave. Later that spring we camped on the beach at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, and the next day drove across the Camargue looking for pink flamingos, and only just making it to Arles before running out of petrol.

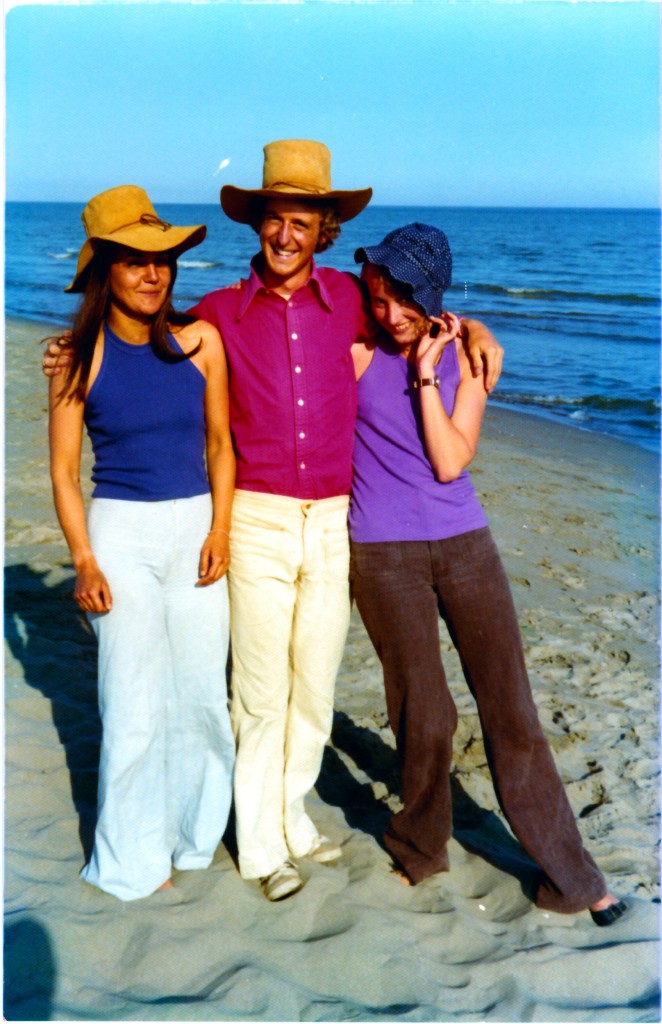

At Easter I went home and bought a pair of tight purplish brown jeans that even Claudia approved of. The anchor trousers were consigned to the bottom of my trunk.

On the beach at Les Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, wearing the new brown jeans

Aww how brave you were . Fabulous read xxx

The attitude to language teaching has certainly changed. At my school (a comprehensive), Latin and French were taught in exactly the same way. The purpose of learning a foreign language was in order to read the great literature of the language in the original, not to have conversations with foreigners!

Exactement!

I don’t remember other students having ‘years abroad’ and wonder if they may not yet have become established in the 1960s. I would have been fearsomely jealous. Certainly, selecting Marseille was very brave – and a huge challenge to the wardrobe!

My own ‘field placements’ were much more prosaic on my Social Admin degree ( would now be social policy) yet the course leads were very visionary for their time, I had placements in Day Nurseries in Manchester; a residential setting – I chose Bristol University Settlement; and a social work dept. – I chose to live at home and work for Sussex, following a children’s social worker around, agog at the problems on my own doorstep. Most dramatic for me however, was meeting a requirement to work on a factory floor and I and 3 other southernern women students worked in a South Manchester cake factory on a conveyor belt – all women on the belt with hair in nets, and all male supervisors in white coats. This was a very testing time in more ways than one, and I learnt first hand about class and gender. I never ate those cakes again!

I think most Modern Languages degrees offered this and some even required it, but not Oxford! I did not actually choose Marseilles but was placed there by the Central Bureau for Educational Visits and Exchanges. Rather late in the day, in fact, and I almost did not make it as I had been put on a reserve list. Fortunately for me, the assistante allocated to this particular lycée took one look at the place and got on the next train home! I think Oxford students were not a priority as our year abroad was not compulsory, so they placed the others first. And then who knows what the tutors put in my reference, given they did not want me to go (the danger being that I would ‘get out of the habit of academic work’ – they must have realised my grasp on this was pretty tenuous).

Your experience in the cake factory sounds as if it was formative and important – as you say – class and gender in four weeks…. And your course sounds so much more like an education than mine!